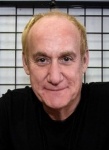

Film, TV, and comics writer Jeph Loeb kicked off the ICv2 Comics and Media Conference (presented in association with San Diego Comic-Con last month, see “ICv2 Comics and Media Conference”) with an inspiring travelogue recounting both his personal journey and the path of Hollywood and the comics industry, and how they all came together.

He introduced his remarks by noting the changes at Comic-Con. “Look at what’s happened to this convention,” he said. “Once upon a time it was in the basement, not unlike the cliché of who the comic book fan is, a guy who lives in the basement of his mother’s house. It’s now grown into something that has over 100,000 people, and gigantic television and movie displays. The first time I was really aware of it was when the Transformers movie brought an entire sixteen wheel truck into the convention center, and I realized that comics aren’t just for kids any more.”

Throughout his remarks, Loeb stressed how comics have become the myths of our culture. “These are modern mythology. These are the legends we grew up with and the legends we’re teaching our kids and our kids’ kids. And I’ve been lucky to be part of this process.”

Loeb recounted his personal journey as a kid growing up with Archie, and the Batman TV show, which he notes was, “for all intents and purposes, a satire. This was how people saw comic books. They were still things that children read. How was that going to change?”

Loeb talked about how his bond with comics was formed, as he realized that he needed multiple issues to track the stories about Superman, and then found Marvels and a new connection.

“This was a world that made sense to me, and this was a world that would then start to grow on those of us that were out there in the creative community. It was a world that was made out of black and white. It was a world where heroes won and the villains lost. It was a world where divorce for a child was something that I couldn’t deal with, but I could deal with in the comic books.”

Loeb also recounted how his comic-reading ritual still arouses strong memories, and contributed to his creative processs.

“You may remember the ritual. It’s a ritual that some of us still have. I would get my comics, which at the time was just whenever they came out, it wasn’t Wednesday.

I’d bring them up to my bedroom along with the lunch that I had made, which would have been cream cheese and jelly, potato chips, a glass of whole milk, and a chunk of salami. And I would lie on the floor of my bedroom, where there was a red carpet, and I would read comics with my feet up in the air. To this day when I read comics I remember the smell of that salami, the taste of the cream cheese and jelly, and the music that was playing in the background. Comics have away of being a touchstone for you, in the same kind of way that certain record albums take you back to a certain point in your life…. And again, as a creative individual, these were really things that changed the way that I looked at comics as a creative entity.”

The next milestone for Loeb was having a letter printed in the comics, and making a connection to the creators by the response he got. “These pieces of paper, the letter that said, ‘Thanks for your thoughtful letter,’ the postcard that was signed by the bullpen, and the No Prize, were ways that Stan Lee and Jack Kirby and Flo Steinberg and whoever else was running around that office reached out and told me as someone who was reading their stories that I mattered.”

Loeb also talked about discovering that a relevant topic like drugs could be talked about in the comics, and about the revelation that was the art of Neal Adams. “I hadn’t really realized how important the artist was to the medium. This work was the work of Neal Adams, who would change, in many ways, the way people looked at comic books. They were no longer people that were larger than life, that had huge muscles, that were something between Popeye and Hulk Hogan. Neal drew people who looked like people. He did it without photo reference, he did it just with the magic that he had. And what that meant was that more and more what you were looking at when you looked at comics was that you were looking at storyboards. You were looking at things that were going to become movies, and television, and animation. And that’s when we started to see it, whether it was Wonder Woman, and then later in the Hulk. You were starting to see the line blur.”

Loeb’s epiphany on comics and film came through the first Superman movie. “But then, everything changed, and for me, this was the pivotal moment where comics and the motion picture industry met each other. And that moment was when they told us that ‘you’ll believe a man can fly.’ It challenged you to go to the movie theater, and believe a man could fly, that you could actually be part of something that was as simple, and at the same time as magical, as what was going on in comic books. And sure enough, you believed it. There was Christopher Reeve flying right out at you, carrying Lois, holding up the helicopter, flying. And in that moment, everyone who went to see this film realized that Superman was somebody that could be, for want of a better expression, real.”

From there, it was a progression through the 1989 Batman film, which used “A” talent to get a great result from the property that had been parodied so successfully on 60s TV, and an indirect path from there to a Flash movie script that never got made and meeting DC’s then CEO Jenette Kahn, who asked “If you’re not going to write a movie for us, would you like to write a comic book?”

Loeb described his reaction. “This was like Santa pulling up at the house and saying ‘I missed you last year, but I’ve got an American Express Black Card, and I’ll take you to FAO Schwarz and get you whatever you want.’”

So Loeb started writing comics. Meanwhile, another watershed moment occurred with the first X-Men movie, which would test the question of whether a relatively new comic property, and one that featured multiple superheroes, could be successful. “The question was could

On TV, Smallville was in development, based on a graphic novel by Loeb and Tim Sale. It was a different approach to the Superman character, but one that worked.

“Certain liberties were taken in terms of continuity, and we all signed off on it. It was ok because at the end of the day, the core values of that time, the idea that Pa Kent and Ma Kent, living on a farm, had brought up this boy as a normal boy to prove that he could still be a human being at the same time as being Superman, came through. It was something that I was really, really proud to be involved with.”

The first Spider-Man film kicked things up a notch in

“The thing that would change everyone’s life in

The movies of 2008, also produced big changes. Iron Man was not well-known to the public, and testing showed that most people believed the character was a robot. Again, the “A” talent saved the day.

“What Robert Downey Jr. brought to that role was the cool factor, and now all of a sudden in addition to watching movies that were cool, the people in the movie were cool. And those people would then go on and make all of us watching the movie feel cool.”

Dark Knight was important because of the level of its success and the number of people it exposed to comic characters, Loeb argued. “When you reach that many people you’ve told a story that touches the lives of that many people. And while comic book sales don’t necessarily reflect the fact that that many people are actually aware of what’s going on, they are. The mythologies, the legends, are being carried on.”

Like the great writer he is, Loeb concluded his remarks by bringing it all back to his underlying themes. “Now the stories of your youth and the stories of the future blended together and became the myths and legends of our days. And now comics are the primary source for stories that are in development for television or for movies. Comics aren’t just for kids any more. You’ll believe a man can fly, and so do I.”