Rolling for Initiative is a weekly column by Scott Thorne, PhD, owner of Castle Perilous Games & Books in Carbondale, Illinois and instructor in marketing at Southeast Missouri State University. This week, Thorne explains game packaging.

Rolling for Initiative is a weekly column by Scott Thorne, PhD, owner of Castle Perilous Games & Books in Carbondale, Illinois and instructor in marketing at Southeast Missouri State University. This week, Thorne explains game packaging.I had the opportunity to try a game designer's new card games earlier this month. The games played smoothly and in general, I liked the card art. However, I opted not to bring them in for one simple reason: the only packaging was a strip of plastic shrink-wrapped around them holding the cards in place. No box, no clamshell, nothing, so I passed. If you want to sell any product (with the possible exception of live animals and delicious fruits and vegetables), you need packaging.

Packaging serves two basic purposes: functional and promotional. The functional purposes of packaging are to allow the customer to transport it, protect its contents and give needed information about them.

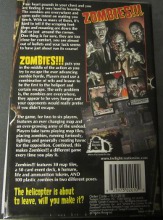

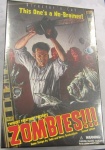

Consider consumer products. Could you transport liquid laundry detergent or toothpaste home from the store if it did not come in a bottle or tube? This is the first function of the package, to hold the contents together conveniently. While carrying an RPG like 13th Age or FATE home is relatively easy (though try getting one home without that handy binding), imagine taking home a board game like Settlers of Catan or Zombies!!! without the box. Pieces and cards all over the place!

The second thing the package does is protect the contents. Even something as simple as a deck of Once Upon a Time cards needs a package. If you just put them out on the shelf, they will get dirty, shelf-worn, even torn. The box, or clamshell, or case, protects them from normal damage.

The third functional thing the package does is provide information about the contents. In the case of toothpaste, the customer wants to know how many ounces, is this tartar control or whitening formula, gel or paste? Consumer protection laws for consumable items require a list of ingredients as well. You find that information on the package. Though ingredients are not necessary in the case of a game, the customer wants some basic information: how many people can play, what ages are suitable, how long should a typical game take, what is inside the package. This last is important because the customer typically cannot open the box to see the contents and stores may not want to open it if they do not have a shrink-wrap machine. (If a store does not have a shrink-wrapping machine and the customer decides not to buy, the opened game is now worth less in the eyes of the next customer.)

In terms of promotion, packaging can do two main things: make your product stand out on the shelf and sell it to the customer. Steve Jackson Games is a prime example of using packaging to make its products stand out, purely through box size. As I mentioned in previous columns, I used to think SJG was wrong for packaging Munchkin in such a large box. Time proved me wrong and over the years; SJG has moved away from the small tuck boxes in which it packaged Chez Geek and Illuminati. Today, those games, and others, come in boxes the size of the Munchkin box, the easier to stand out on the shelf.

The packaging also should sell the product to the consumer, tell them why they should buy it, why they are going to have fun playing it, how play works. While the FLGS probably has someone who can tell the customer about the product, if a game makes it to the shelf of a Target or B&N, no staffer there will work to sell it. The poor game package is on its own. Bland doesn't attract attention, bright and attention-getting does.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com