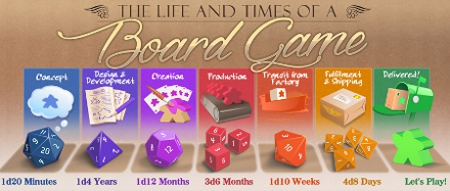

The Life and Times of a Board Game is a new tabletop game industry series written by Dan Yarrington, founder and CEO of Game Salute. Yarrington has nearly 20 years professional experience in the game industry, having founded the Myriad Games retail store in 1996. This week, Yarrington kicks off his new column series on "The Life and Times of a Board Game."

The Life and Times of a Board Game is a new tabletop game industry series written by Dan Yarrington, founder and CEO of Game Salute. Yarrington has nearly 20 years professional experience in the game industry, having founded the Myriad Games retail store in 1996. This week, Yarrington kicks off his new column series on "The Life and Times of a Board Game."Welcome back to The Life and Times of a Board Game, a new series about all the incredible things that happen in the tabletop game industry. For this installment, Dann May joins us to discuss the first phase of the Life and Times of a Board Game--Concept. Dann May is the Chief Creative Officer at Game Salute and has helped to bring dozens of games to life, so it's great to have his perspective on Concept.

First off, thanks to everyone for the feedback to the initial article (see "The Life and Times of a Board Game: A Cordial Introduction") that introduced the series overview. We've taken all that feedback, both online and in person at shows like Essen Spiel and BGG.con and laid out the plan for the next steps in the series. In each installment, we'll talk with someone from the tabletop games industry about the details involved in that stage of the Life and Times of a Board Game.

"I've Got an Idea!"

Every game begins with an idea, usually a small kernel of an idea, asking questions like:

"Wouldn't it be awesome if we had a game like _____?"

"What if we mixed ______ and _______?"

"How come there’s not a deck-builder that does ______?"

"This came would be awesome if not for _____!"

This is the simplest part of the entire Life and Times of a Board Game and it happens extemporaneously all the time: around kitchen tables, at diners at 2AM, at conventions, while traveling to and from gaming destinations, while playing games, while watching movies, while reading books, while dreaming, and everywhere in between.

"The Power of a Good Idea"

There is power in a good idea. An idea can be the foundation of a successful project. But ideas evolve, so the initial kernel of an idea could really be anything. It is the nurturing and growth of the idea during the consideration process that creates a valuable concept. The original core of the idea might persist as the core of the project, but it might just be the inspiration for another idea and then another that eventually leads to the final concept. Basically, you could start working with one idea and end up with another--the main thing is to start the work of actively thinking.

We have the somewhat tongue-in-cheek measurement of 1d20 minutes for Concept. While the core thought, that "aha!" or "what if…" premise can be drummed up in that short amount of time, the actual process of fleshing out a concept and seeing if it will work takes longer. It takes more than a good idea to make a great concept for a game. It takes years of life experience and knowledge before that moment to generate a truly worthwhile idea. The spark of an idea, like a seed, will be more potent if the person curating and nurturing the idea has been keeping an eye out, daydreaming, researching, watching what others make, admiring nature, reading, making connections, talking to people, learning from past failures, playing around, and all sorts of activities that will inform their thought process. All of those background activities lead to an idea that has more potential than a mere figment. So there is a time before an idea (germination), and time after the idea takes root (growth), both of which are considerably deeper and longer than the initial moments of inspiration.

"What Makes A Great Idea?"

Everybody can have good ideas. Most folks have mostly mediocre ideas. And even the most creative folks have a plethora of useful, entirely awful ideas. The trick is defining what you mean by a "great idea" and separating the good from the bad, the great from the mundane. If we define a great idea as being one that leads to creating a critically praised, outstanding, impressive, financially successful product, then here are some aspects we can focus on:

â— The idea needs to have a certain originality, and be able to stand out in the marketplace of ideas, but it also needs to have enough familiarity that people are able to connect with it

â— The idea needs to be feasible to develop and produce

â— The idea needs to be internally consistent. That means it needs to have a degree of clarity to it, which is why often the best games are created around a core experience the designer keeps returning to while crafting the concept. An idea that is overly complicated will often fall apart because different conflicting aspects of it cannot be resolved together into a cohesive entity. If it doesn't fall apart entirely, the game will end up as a product with an unfocused, fractured or incomplete quality.

"How Do I Craft Ideas That Will Last?"

It's different for everyone, but here are some consistently successful approaches that seem to work for a lot of designers.

1. Make What You Love. Take an idea that is important to you, something that reflects something important in your life. Examples include wanting to make a game to play with your wife or kids, or to use with your students, or to share something about your life.

2. Bring Something New To The Table. A lot of creativity is about making new connections, so introducing something from one area of interest to game design can be fruitful. The simplest form of this (which has been used to good effect recently) might be asking what you could bring to a board game from what you enjoy about video games. But it could extend well out beyond games into books, movies, macrame, or pretty much anything that helps you get your geek on.

3. Build A Better Mousetrap. What does an existing game or game genre need to make it better? What's missing from a game experience? How can you strip something down to the essential core and rebuild it with a new twist?

4. The Pearl. In this scenario, you're an oyster and a speck of sand gets in to your shell, which you build a pearl of an idea around. This is where your starting point is not something you like, but rather something that aggravates you. What's broken about a game or genre that you could fix?

5. Doodling and Free Play. Some of the best ideas come just through puttering around and mucking about. Making up games on the spur of the moment, actually through physically playing with components, interacting with other people and environments and letting your mind wander.

6. Reach For The Stars. What would be the most awesome game ever? How can you make that a reality?

7. Game for the Moment. What would I ideally want to play right now? How can you make a game to suit this very moment and situation?

"To The Design Studio!"

Now that you have your massive notebook of ideas, it's essential to remember the following when you're considering taking an idea from Concept to Design and Development.

You need to really like the idea, because you're going to have to put in a ton of hard work and monotonous testing and frustrating redesign in order to make it any sort of semblance of reality. You'll run into hurdles and roadblocks and brick walls that will put your passion to the test and have the potential to snuff out the flame of innovation and inspiration that brought you to the idea in the first place. So make sure you truly love the concept before you move forward.

Thanks again to Dann May for joining us for this week's article and contributing to these great ideas!

I invite each and every one of you to participate in this by writing in comments through the site, emailing me at Dan@GameSalute.com, following and tweeting @GameSalute, or messaging me on Facebook. I'm looking forward to sharing your stories through this series, so don’t hesitate to send in your suggestions and requests. As we continue on, we'll explore all the amazing steps it takes to bring a game from concept to reality.

--Dan Yarrington is founder and CEO of Game Salute and the founder of Myriad Games. He is an enthusiastic husband, father, brother, son, and avid and perpetual game evangelist in all these roles.

The opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff of ICv2.com.